Mike Foy waited nearly 10 years to revive his bold plan to save Wisconsin’s deer herd from chronic wasting disease (CWD), but since floating his ideas publicly in late January he’s mostly heard only anguished cries from drowning doubters with no rescue plans of their own.

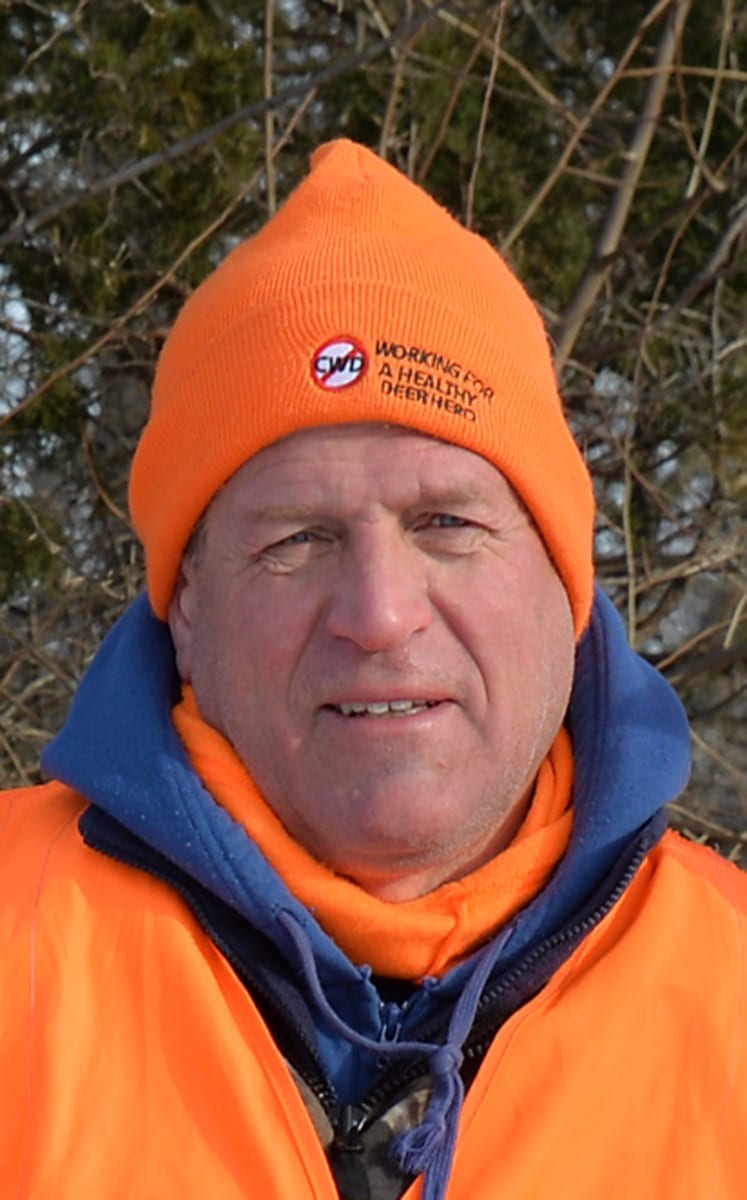

Foy, 61, retired in September after 30 years as a wildlife biologist and supervisor with the Department of Natural Resources. When addressing the 78th Midwest Fish and Wildlife Conference in Milwaukee in late January, Foy updated a CWD plan he first shared in 2008 at the group’s 68th conference.

Mike Foy spent half of his 30-year DNR career dealing with chronic wasting disease. He thinks it’s time to “incentivize” hunters to shoot more CWD-carrying deer each year than the herd can produce.

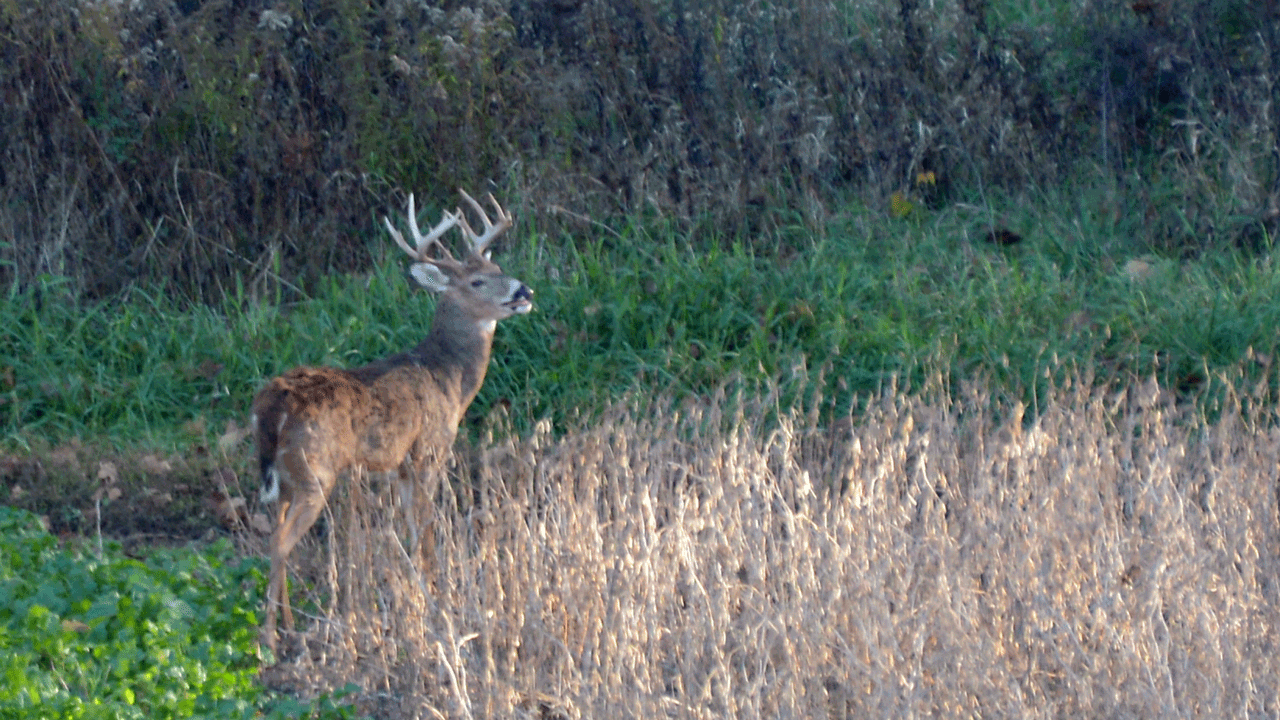

Foy suggests significant pay for hunters and landowners each time they deliver a CWD-positive deer. If your deer isn’t sick, you don’t collect a dime. Call it an incentive. Even call it a bounty. But don’t call it a lottery. This isn’t about chance. Hunters who are serious about getting paid won’t hunt randomly. They’ll study CWD prevalence maps, identify areas with the greatest potential for payoffs, and focus there.

When my colleague Paul Smith at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel shared Foy’s plan Feb. 1 and suggested $1,000 rewards, skeptics asked if sick deer would wear hospital bracelets to identify themselves. Others sniffed that bounties are affronts to the North American Wildlife Conservation Model, even though the model wasn’t conceived for tackling diseases. Still others warned of “unexpected consequences,” as if imagined evils might trump the realities of endemic brain rot.

Some even suggested Foy transplant wolves to southern Wisconsin to prey on sick deer. They assume CWD remains rare in the Northwoods, and further assume wolves explain why. Unfortunately, they can’t explain the absence of wolves and CWD in most Southeastern and Northeastern states.

Foy absorbs the cynical reactions and shrugs. He spent the final half of his career dealing with CWD’s frustrations. After a doubting, impatient public squelched the Wisconsin DNR’s initial plans to quell CWD by quashing deer from 2002 through 2006, the agency quit suggesting experiments and testing theories to stop the always-fatal disease.

Yes, DNR administrators let Foy display his bounty-based idea on a poster in a side room at the 2008 Midwest conference, but few studied it. Afterward, agency brass consigned the plan to a dumpster, mumbling, “Let us never speak of this again.”

Retirement frees Foy to resume speaking. He notes that Wisconsin recently pledged $3 billion for 3,000 high-tech jobs near the Illinois border, and proffered big tax breaks for 600 jobs for a paper company south of Green Bay. Why then blow past 15,000 jobs affecting countless businesses and hunting families staked to Wisconsin’s $1.3 billion annual deer hunting economy?

Foy also notes taxpayers gave $392 million for Milwaukee’s Miller Park, $295 for Green Bay’s Lambeau Field and $250 million for the Milwaukee Bucks’ arena in recent years, and yet the state’s wildlife agency fretted about spending $780,000 in 2017 on less than 10,000 CWD tests. Realize, too, that a state wildlife agency without deer-license revenues – which provide about 75 percent of its annual wildlife budget – is like a Big 10 school’s athletics budget without football and a huge stadium.

Foy’s plan sounds sensible and practical. True, CWD-carrying deer don’t look sick until their final weeks, but agency staff once shot CWD-positive deer at far higher rates than did regular hunters: 4 percent vs. 0.8 percent in 2005, and 2.3 percent vs. 1 percent in 2006. How? By using disease data to focus on high-prevalence areas.

“It’s all about statistics and probabilities,” Foy said. “Scientists used similar calculations to find the USS Scorpion (lost May 1968, found October 1968) and SS Central America (lost 1857, found 1988) on the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean, so don’t tell me we can’t use Bayesian search theories to find sick deer in Wisconsin woodlots.”

Foy suggests the DNR hire a smart, young, UW-trained researcher to resume making CWD prevalence maps, which the agency hasn’t updated since 2013. It would share the maps with Wisconsin’s orange army, which covers more ground than the agency ever touched when its shooters used similar maps to guide their efforts.

Would bounties – financial incentives – focus more hunting pressure on areas with higher CWD infection rates?

“The plan would have to show results,” Foy said. “We have the firepower, but we need to deploy it in the right places.”

How much would the program pay for each CWD case? That answer requires basic research to estimate the number of sick deer in the woods, how much effort goes into each CWD kill, how much landowners want for access, how much butchers and taxidermists want for collecting samples, and other participation factors.

“No business sets the price of its widgets without analyzing the market,” Foy said. “In 2008 I might have said $5,000 per confirmed case, but we have far more CWD cases now. Good hunters in highly infected areas no longer need eight days for a realistic chance of shooting a diseased deer. Would $1,000 be enough? I don’t know, but we stand to lose $1.3 billion annually by doing nothing. Paying $10 million for 5,000 confirmed CWD cases seems like a fair annual investment. It wouldn’t be cheap. We’d explore every possible funding source in the public and private sectors.”

Infection rates for 2.5-year-old bucks have hit 50 percent in some parts of southern Wisconsin.

To work, hunters must remove more CWD cases each year than the herd creates. “To drive CWD toward extinction, we must shoot 20 to 50 percent of the herd’s sick deer annually,” Foy said. “I doubt we’re removing even 20 percent with our current approach.

“The right financial incentive is the amount necessary to remove those numbers. You could even adjust incentives based on a deer’s potential to spread disease. Maybe you’d pay more for a sick yearling buck that’s likely to disperse than a 4-year-old buck that’s likely to stay home.”

Foy envisions the DNR and county deer advisory councils still determining kill quotas. The goal is a stable herd with declining CWD rates, not a tiny herd with high infection rates.

“If you put this in financial terms, we aren’t even paying the interest due right now on CWD, let alone its principal,” Foy said. “We’re getting further behind every year. If we can’t pay both, we’ll lose everything.”

Doing nothing has ramifications beyond Wisconsin. CWD is also present nearby in Illinois, Iowa and Minnesota. Those three states are taking more aggressive approaches than Wisconsin so far, but their efforts might be for naught if Wisconsin’s CWD rates keep spiking. Some areas already have 50 percent infection rates in bucks 2.5 years and older.

“We need everyone working together,” Foy continued. “Yes, prevention is the key. Keep it out if you don’t have it. But what’s your plan if you have it? I’m offering a viable plan. What’s yours?”

By

By