Those who grew up with compounds and releases think there’s voodoo involved while shooting fingers and without sights and let-off. They believe this because they can’t imagine shooting without mechanical crutches. Shooting traditional bows well is more difficult because it’s difficult for most to let go of those crutches, but also simpler because of the lack of these trappings. Trad-bow limitations come through an inherently less efficient machine (less energy, speed) but also the amount of work shooters are willing to invest. For example, with better shooting-fundamentals understanding and more productive practice routines my traditional-bow maximum effective range now matches compound capabilities of 20 years ago. To succeed in traditional archery a slightly different set of rules is required.

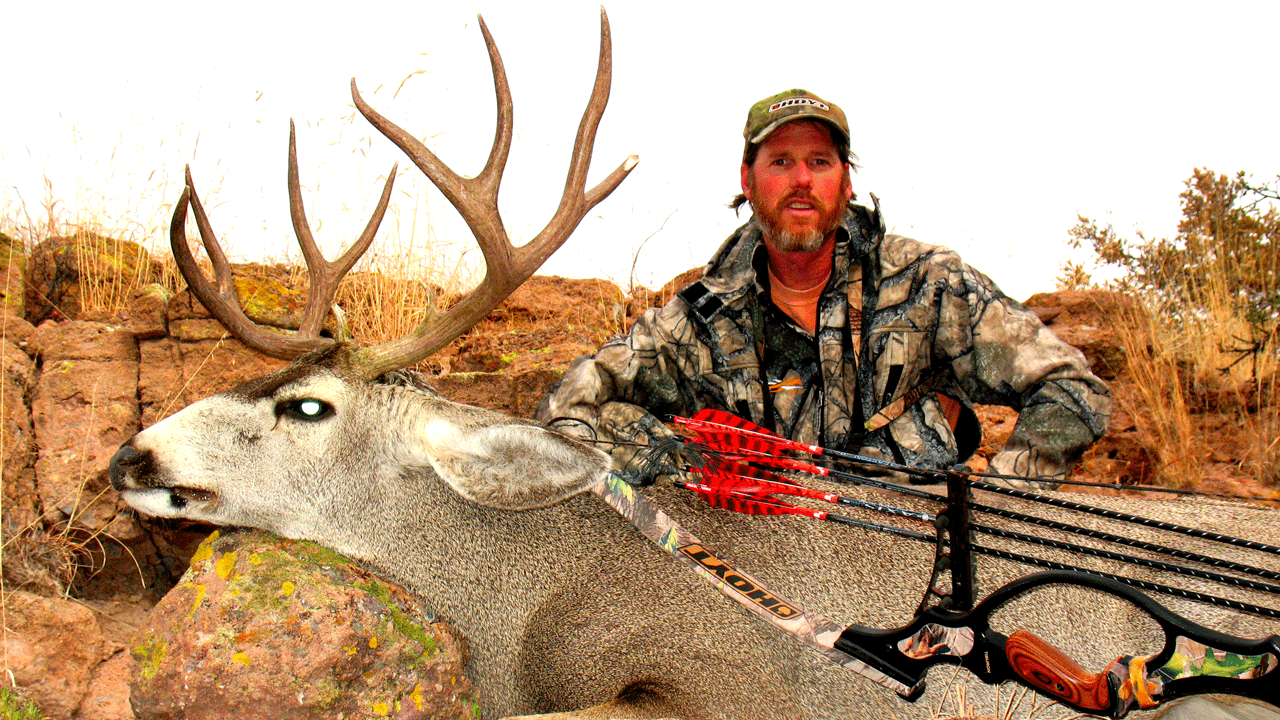

The author made good with a solid shot on this muley buck in the open country with his recurve.

Purchase a Bow That Fits

The fact you comfortably shoot 65-pound compounds doesn’t mean you should order a traditional bow anywhere near those specs. I shoot 70-pound compounds quite comfortably, even from cold treestands. I shoot recurves marked 50#@28” (50 pounds at 28 inches). Besides lack of let-off, quality traditional bows gain 3-4 pounds for every inch drawn. At my draw length those 50@28 bows pull around 56-58 at my 30-inch draw. I could pull more, but handle these specs effortlessly, allowing me to concentrate on settling in and “aiming,” not struggling to keep a heavy bow at bay and encouraging the bad habit of snap shooting. If your draw length is shorter, more poundage may be fitting, while those with longer draw lengths must keep the 3-4-pound rule in mind. Too, purchase bows that fit your physical stature, a 56-60-inch tip-to-tip recurve for those with 28-29-inch draws, 62-64-inch recurves for those with 30-plus-inch draw lengths. This allows bows to work efficiently; limbs not under-flexed with a too-short draw length or overstressed with a too-long draw length.

The right gear, coupled with consistent shooting form, are the foundations for success with a traditional bow.

Shoot Heavy-For-Spine, High FOC Arrows

Recurves and longbows are relatively inefficient machines—in relation to compounds at least. Less poundage factors, but pound for pound these primitive “springs” can’t match modern compound limb/pulley systems. An average hunting compound produces 65-85 foot pounds of energy, while hunting-weight trad bows produce 45-55. You compensate with momentum to assure broadheads drive deep into game. Momentum is enhanced not by speed, but arrow weight.

Carbon is welcomed for traditional arrows, as nothing penetrates better due to superior paradox recovery and less energy-robbing wound-channel slapping. The trick is choosing heavy-for-spine carbons weighing 10-12 grains-per-inch (gpi). Arrows such as Black Eagle Archery Deep Impact, Easton Injexion or Full Metal Jacket and Carbon Express PileDriver PTX, for example. Others feature added layers, including wood-grain graphics (Beman CenterShot, Easton Traditional or Carbon Express Heritage), or those purpose-built for added mass like the Alaska Bowhunting Supply Grizzly Stiks.

You should also load the front of trad arrows for extreme F.O.C. (Front of Center) balance. Adopt steel or brass inserts (or add steel weights from Precision Designed Products; pdparchery.com), or heavier broadheads. Standard compound heads weigh 100-125 grains. Traditional arrow heads in the 145-200-grain class are par, or 125-grain heads combined with 50-100-grain brass inserts. Front-heavy arrows not only fly straighter, but penetrate better. The heavy front literally drags trailing arrows through wound channels.

Shoot Cut-On-Contact Broadheads

Limited single-string energy also demands highly-efficient broadhead designs. Classic one-piece-welded broadheads like Zwickey Black Diamond and Delta (2 and 4 blades), Simmons Sharks, or Snuffers (3-blade) are still viable today, glued on to aluminum or steel screw-in adaptors. Modern screw-in heads like Steel Force’s Phatheads or DirtNap Gear, as examples, are precision made and extra tough.

All of these are sleek cut-on-contact designs that slice the moment they touch hide, sliding through muscle and vitals effortlessly. They’re also tough enough to split and smash bone and remain intact. In traditional archery (unless bowhunting turkeys) replaceable-blade and mechanicals are anathema.

Dave Oligee of Simmons Sharks and a bull he killed with his deadly cut-on-contact broadhead.

Tighten Shooting Form

Whether instinctive shooting or gap shooting (using arrow tip as “sight pin’) you have no let-off and solid rear wall to force correct draw length. Anchor must be precise and absolutely repeatable or you’ll pull slightly more or less draw weight each shot. When shooting without sights, and especially peep, your anchor becomes your rear sight – another reason it must be dead-nuts repeatable. A 100 percent natural and repeatable anchor is a product of solid overall shooting form. You can get sloppy while shooting compounds, using those crutches to muddle through with acceptable results. If you expect to shoot recurves or longbows well beyond 15-20 yards, shooting form must become flawless. This requires going back to basics for some (including hiring a shooting coach when needed), and strict discipline for even experienced shooters.

Your shots and shooting form must be tight when you try turkeys with a trad bow.

I find blank-face shooting helpful. Blank-face shooting means stepping close to a target face covered in blank paper. The idea is complete, results-free shooting. You’re not concerned about hitting a mark or groups. It’s about feel, envisioning and instilling what perfect shooting form feels like to the point of automatic reflex. Traditional shooting isn’t an excuse for poor performance, as some seem to believe. Poor traditional shooting comes from poor practice regimens and lack of discipline.

Concentration Switch

Fred Bear was serious when it came to the concentration involved with shooting a traditional bow.

Good traditional shooting depends on learning to turn concentration on and off at will. Fred Bear said of shooting instinctively, “This concentration must be overwhelming. The whole body from the toes to the top of the head must be involved in every shot.” Mental visualization is a huge part of this, envisioning successful shots start to finish. Picking a spot is also imperative, as the old adage of “Aim small, miss small” is definitely at work. I take this a step further. Instead of seeking a physical spot on animal or target, I create my own and place it wherever I want. Some have suggested envisioning something familiar; a lucky coin or worry stone. I envision a glowing laser spot.

I place this spot on the target exactly where I want to hit and invest every ounce of concentration on that point, burning a hole through it, allowing the shot to happen in its own time, continuing to bore a hole through it and hold steady after the arrow is away, not releasing that concentration until arrow pierces target. With a perfectly-fit bow, well-balanced arrows and solid shooting form it does seem a certain brand of magic when that arrow covers your spot.

By

By