LAST UPDATED: May 8th, 2015

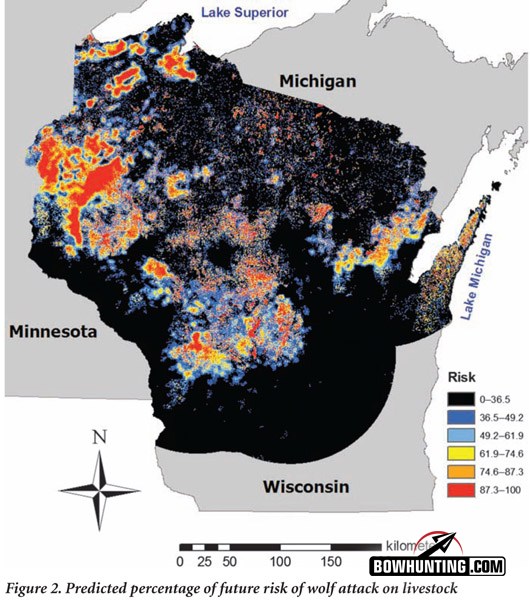

When North Woods farmers consider whether to add land or livestock to their operation, or whether to plant deer-attracting crops, they might want to consult a new “risk map” to determine it they’re increasing the risks for wolf predation.

This map was developed by researcher Adrian Treves at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The map and the research behind it was explained in the June issue of “BioScience,” a scientific journal.

In 2010, wolves were blamed for killing livestock on 47 farms in Wisconsin.

After analyzing 133 documented wolf attacks on livestock between 1999 and 2006, Treves concluded one-third of the area in a pack’s range is at risk. He also found about 10.5 percent of that area faces a “serious” risk from wolves.

He then used that analysis to predict with 88 percent accuracy where wolves would attack livestock from 2007 through 2009.

Wisconsin’s North Woods and central forests are home to at least 800 gray wolves. In 2010, wolves were blamed for killing livestock on 47 farms. Those attacks included 63 cattle killed (47 calves), five cattle injured, six sheep killed (four lambs), one goat injured, and six farm deer killed. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources believes 25 to 27 wolf packs — 14 percent of the state’s 181 packs — and two to four loners/dispersers made the attacks.

Since Wisconsin began paying people in 1985 for pets and livestock killed by wolves, it has paid out $1.08 million in compensation.

In Wisconsin, the DNR compensates people for pets and livestock killed by wolves, with payouts totaling nearly $204,000 in 2010. Since the program began in 1985, the Wisconsin DNR has paid out $1.08 million in compensation.

That sum includes $437,020 for lost, killed or injured calves and cattle; $402,120 for killed or injured bear-hunting hounds; $56,040 for killed or injured pets; and $188,000 for other livestock, including turkeys, chickens, deer, horses, donkeys and a llama, pig and goat.

Treves found attack sites typically feature more open habitats of mixed forest and pastures within range of a wolf pack, with wolves usually targeting livestock farther out in pastures, not near their forested edges.

By merging his attack analysis with satellite imagery that pinpoints habitat types, Treves developed a color-coded map to predict wolf attacks on Wisconsin livestock. The six colors assess each area’s risk from high to low. Not all color-coded areas currently hold wolf packs, but the map assesses their risk for livestock attacks should wolves move in.

The science behind the map could be applied to develop similar “risk maps” for other Great Lakes states with wolf populations.

Two timber wolves cross a farmer’s field in northeastern Wisconsin in May 2011.

The risk map has at least two immediate applications. First, farmers will be able to call up the map on their computer, input an address, and zoom in to see the property’s potential for wolf predation. This could help them decide whether to buy certain lands or move livestock to specific pastures.

In addition, it could help them decide whether to plant food plots or crops highly attractive to deer. More deer might improve hunting for a farmer or property owner, but an influx of deer would likely attract wolves. Once there, the wolves might discover it’s easier to kill livestock than whitetails.

That leads to the map’s other use: Helping wildlife managers decide where to focus hunting pressure on wolves, assuming Wisconsin eventually obtains that responsibility from the federal government.

Adrian Wydeven, the Wisconsin DNR’s wolf biologist, said that won’t happen until the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service removes Great Lakes wolves from the Endangered Species List. But Treves’ risk map scientifically documents wolf behavior and demonstrates the DNR is prepared for control measures.

Treves said control efforts are less expensive and more successful when biologists can pinpoint high-risk areas for wolf-livestock predation.

“To date, people have been largely unable or unwilling to discriminate between individual culprits and non-culprits when addressing problems with wild animals,” Treves wrote in his “BioScience” article. “Risk maps point the way to more selective interventions in conflicts between wild animals and people.”

That means working with more landowners before wolves become a problem. Wydeven said techniques like “fladry” seldom work if wolves are already targeting a farm. Fladry means surrounding an area with a light rope a few feet above the ground, and hanging small flags at intervals. The flapping flags tend to keep wolves from crossing underneath.

Other proactive measures include keeping calves and sick or injured livestock in the barnyard for closer monitoring, and burying dead or butchered livestock rather than dumping them above ground where wolves might come scavenging. Once there, they might switch to live animals.

Preventive measures can’t guarantee a cure, of course, but the sooner they’re administered, the longer wolves and livestock stay apart.

By

By