If the COVID-19 pandemic proved anything, it’s that many Americans are rebellious in nature. Tell us what to do, and an instinctive desire implores us to do the opposite. We don’t always act on this urge, but it exists.

The result is either a begrudged adherence or flat-out rejection. As the pandemic took hold, guidelines encouraged us to stay home, away from others. In true American fashion, we abided, but with a twist. We went hunting instead.

Has COVID-19 been good or bad for hunting? Here’s a closer look at the numbers. You be the judge.

Hunting Participation

A pandemic-inspired fervor for the outdoors is causing an influx of new hunting recruits. According to The National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF), which leverages a 15-state statistical sample to highlight hunting trends in the U.S., more new hunters joined the ranks in 2020 than in any previous five years.

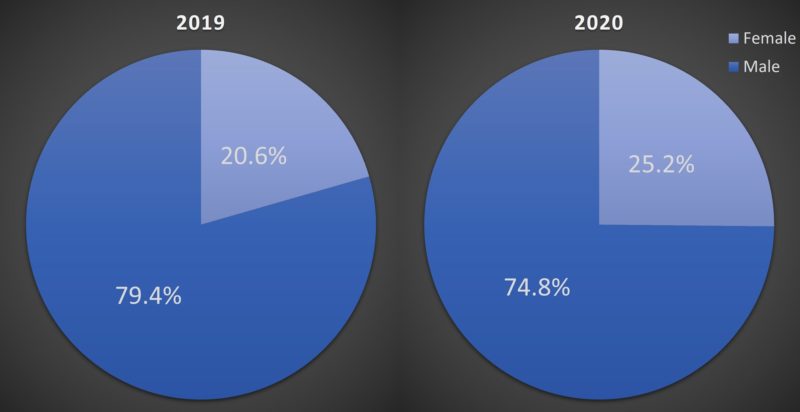

Driven by a staggering 47% surge in new female hunters, new hunting participation was on track to increase by over 20% in 2020. Considering that new hunter recruitment is vital to wildlife management’s long-term viability, these figures bode well for enduring hunting enthusiasm.

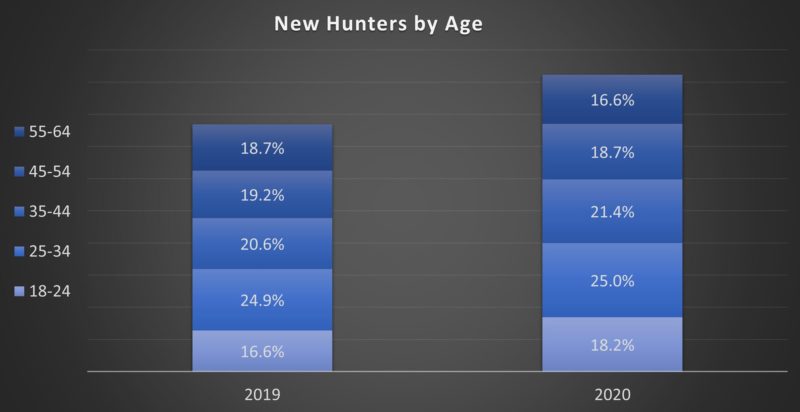

The most promising statistic might be that 43.2% of 2020’s increase derives from hunters between the ages of 18 and 34, up from 41.5% the year prior. New, young hunters bode well for the future of hunting. Maybe, just maybe, this pandemic-fueled surge in hunting-related outdoor activity can reverse the downward trend of years past.

Hunting License Sales

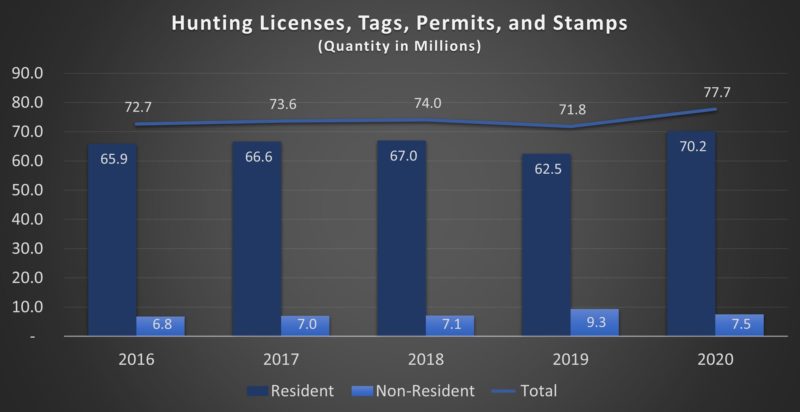

Along with the boom in hunting participation, general hunting activity followed suit. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, hunting licenses (including tags, permits, and stamps) sales experienced an 8% rise in the 2020 calculation year. The substantial increase came from resident hunters, as non-resident hunting sales dropped nearly 20%.

This homebody hunting activity reverses a recent trend. Before 2020, non-resident sales were on the rise, clocking a significant 32% increase over the previous year. 2019’s considerable jump in non-resident sales, although promising, didn’t offset a stagnant, yet overall downward trend. In fact, during the non-resident sales boom, overall sales fell nearly 3%.

The good news here is that the extra revenue from increased license sales funnels directly into wildlife management agencies. More hunting activity equals more wildlife support. Churn will occur, but we can expect hunting participation to retain a large portion of 2020’s growth.

Hunting Success

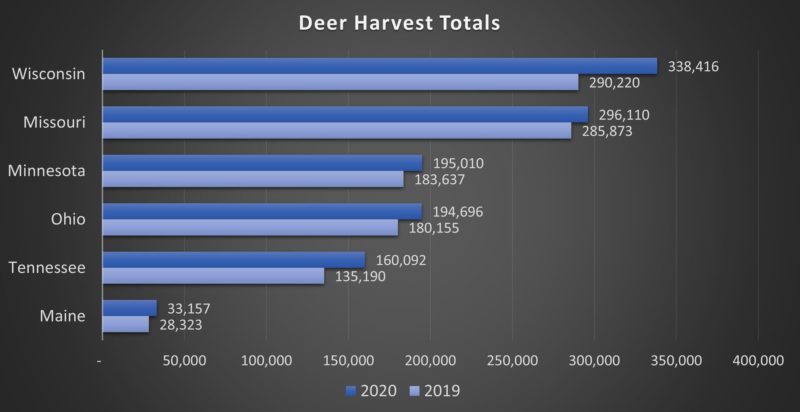

With an increase in both hunting activity and participation, harvest numbers are sure to rise. Figures aren’t finalized, but many states report a considerable increase in deer harvests compared to 2019.

The Missouri Department of Conservation reports over 296 thousand deer harvests, up from 285 thousand the year before. Preliminary 2020 harvest numbers from Maine are their highest in more than 15 years, up 17% from the previous year. Tennessee, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin all follow suit, with considerably increased harvest totals in 2020.

It’s a consistent, albeit not surprising, story throughout most of the United States. Naturally, one should expect harvest numbers to creep up alongside an increase in hunting activity. However, how will this affect the future of hunting? If this recent swell in hunting participation and activity continues, harvest figures will reflect that change. But, when it comes to wildlife conservation, more doesn’t always equal more.

Conservation Success

Speaking of conservation, what about the non-profit conservation groups whose very existence relies upon charitable donations? These wildlife bastions, such as the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation (RMEF) and the National Wild Turkey Federation (NWTF), spearhead nationwide wildlife conservation efforts. The RMEF recently surpassed the eight million mark in habitat acres of conservation work, with no intention of slowing down.

Most non-profit conservation groups receive the bulk of their income from group gatherings, like banquets. In the case of NWTF, gaggles of turkey-supporting folks will shell out their hard-earned dollars to gather around, share bearded stories, and silently bid on hunting swag.

The pandemic hindered these in-person events, crippling conservation groups in the process. At the end of their 2020 fiscal year, NWFT’s income dropped by nearly 16%. The bulk of this decline stems from reduced program services, such as banquets. With group gatherings constrained, how can they make up for the lost income? For now, they’re replacing banquets with virtual events, as well as reducing staff, in the hopes of riding out this germ-infested storm.

Fortunately, funds from the increase in activity and the recently passed Great American Outdoors Act will spur new wildlife management programs, but it may take years before we reap the rewards. Improving wildlife populations through habitat management is a long process. How will wildlife agencies support this influx of hunters? To put it in business terms, can supply outpace demand? Conservation dictates balance. Healthy wildlife requires a thoughtful melding of population and habitat into a sustainable coexistence. No more. No less.

Conclusion

The stats are flooding in. More people are flocking to the sport, and overall activity is up, reversing years of stagnation. On the other side, the pandemic stifled conservation fundraising efforts. Groups such as RMEF and NWTF lost their primary source of income when the pandemic halted group gatherings.

There’s no reason to think the trend of increased activity and participation won’t result in more lifelong hunters. And, as the hunting population grows, accompanied by the eventual return of group gatherings, the survival of conversation groups looks promising.

For all its woes, the pandemic was a bright spot for hunting. It rekindled America’s love for the outdoors. Our challenge is to bridge the gap, ensuring new and existing hunters have ample opportunity to participate. If we all chip in and support conservation groups, practice responsible land stewardship, and most importantly, share our love for the sport, hunting will flourish for years to come. In fact, many years down the road, when we look back on 2020, we may see the pandemic as the event that saved hunting.

By

By