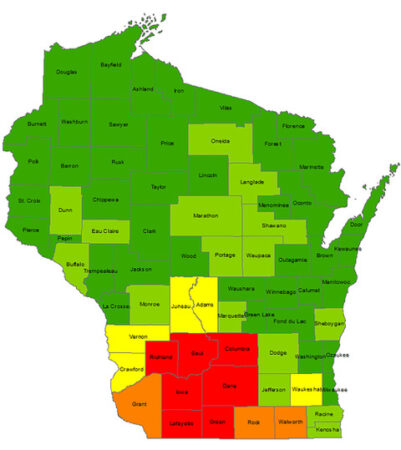

Wisconsin found chronic wasting disease in a record 31 counties during 2022’s deer seasons — including first-time discoveries in Buffalo, Langlade and Waupaca counties.

CWD infections have skyrocketed in the Badger State since 2014, when Wisconsin began its “passive management” approach. During Wisconsin’s 2022 deer seasons, infection rates for hunter-killed deer hovered near 20% and higher in seven counties: Columbia (19.5%), Dane (20%), Iowa (28%), Sauk (26%), Richland (27%), Green (19%) and Lafayette (21%).

CWD skeptics have claimed CWD is a “political disease” in Wisconsin, and that it’s merely a “four-county problem” limited to Dane, Iowa, Sauk and Richland counties near the state capital in Madison. Richland County, however, wasn’t one of the original four. It had one CWD case in 2002, the year CWD was first documented east of the Mississippi River. In fact, Richland County’s lone case seemed a fluke until annual infections hit 11 in 2010, 18 in 2012, and then 66 in 2016. Richland’s CWD tally hit a state-high 375 last fall, from a state-high 1,392 tests.

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources has now found CWD in wild, free-ranging deer in 41 of the state’s 72 counties (57%). Ten counties that previously found CWD did not find additional cases in 2022, but that doesn’t mean the disease isn’t present. CWD tests aren’t mandatory in Wisconsin, and 70% of its hunters have never submitted a deer for testing. Therefore, annual CWD surveillance isn’t done systematically across the landscape.

Richland County, for example, didn’t find one CWD case in 2003 or 2004, even though hunters submitted a combined 3,008 deer those years. That was a lull before the storm. As of early April 2023, Richland County has documented 1,646 CWD cases from 18,329 tests (8.9%) this century. Richland has overtaken Dane County, 1,573 cases from 33,609 tests (4.7%); and is closing fast on Sauk County, 1,701 cases from 21,214 tests (8%); but far behind pacesetting Iowa County, 4,130 cases from 52,334 tests (7.9%).

In other recent CWD news, researchers at the University of Calgary’s veterinary medicine school published a report in August stating its researchers found an “actual risk” that this prion disease can transmit to humans. https://vet.ucalgary.ca/news/chronic-wasting-disease-may-transmit-humans-research-finds

Sabine Gilch, an associate professor and Canada’s research chair in prion diseases at the university, said in a press release: “This is the first study to show the barrier for CWD prions to infect humans is not absolute, and that there is an actual risk that it can transmit to humans.” Prion diseases like CWD attack proteins in the brain, causing clumps to form, and eventually cause death.

The university’s press release notes that previous CWD research has studied hunters who consumed game in regions with high disease rates in the animals, and found no evidence of human infection.

In the U-Calgary study, laboratory mice developed CWD over a period of years and shed infectious prions in feces. The researchers concluded that CWD in humans might be contagious and transmit person to person.

The researchers also found that CWD might show up differently in humans than in animals and other human-specific prion diseases, making it difficult to diagnose with current screening methods for humans.

The study’s lead researcher, Samia Hannaoui, cautions that more research is required, because they haven’t proven animals can transfer CWD to humans. “We’re far away from that,” Hannaoui said.

Researchers in the U.S. also haven’t reached that conclusion, and in recent years have used the word “robust” to describe the transmission barrier between humans and CWD-infected deer and elk. Even so, they don’t dismiss the possibility. That’s why wildlife agencies recommend hunters get their deer tested for CWD and not consume its venison if it tests positive.

Even so, some CWD critics continue to downplay CWD’s spread. One high-profile critic downplayed its presence in Wisconsin in 2016 by noting it had never been found in more than 14 counties in a given year. He was soon proven wrong. CWD was found in 20 Wisconsin counties in 2017, 21 counties in 2018, 24 counties in 2019, 23 counties in 2020, 26 counties in 2021, 31 counties in 2022, and 41 counties overall.

The state appears to be slowly abandoning the “passive-management” approach, maybe because deer hunting’s economic impact on Wisconsin is roughly $1.5 billion annually. For comparison, a study released in 2020 by the Metropolitan Milwaukee Association of Commerce found that the Milwaukee Brewers (Major Leagues Baseball) had only a $2.5 billion impact on Wisconsin the previous two decades. In other words, deer hunting had 12 times the Brewers’ economic impact from 2000 to 2020.

Perhaps in response, the recently released draft of Wisconsin’s 2023-2025 state budget showed that Gov. Tony Evers wants to use $1 million from the general fund for grants to buy deer-carcass disposal sites. Evers also backed $50,000 for CWD education for hunters, and $469,800 to hire six microbiologists for the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s veterinary diagnostics laboratory to speed CWD test results.

By

By