The natural world is in a constant state of flux. That red-hot covert or hunt unit that relinquished plenty of action a few years ago can prove dead as disco tomorrow, due to environmental factors such as regional precipitation levels, livestock grazing, logging activities, utility or fencing projects, or just a general shift in hunting pressure. On-the-ground scouting has always been a huge part of successful bowhunting, but bowhunters visiting distant game country or pioneering new hunting areas don’t enjoy this luxury. Whether starting a season on fresh ground or traveling to foreign habitat to try your hand at Western game or potentially bigger whitetail bucks, researching your hunt area from home allows you to hit the ground running once your adventure begins. This begins at home, well before you pack the truck and head into the field. The whitetail rut is upon us. Strategies come and go at this time of year like no other time. Find the right spot via scouting and you’ll punch more tags. Here’s a look at how to scout for your hunt from your desk.

Time spent scouting at the desk can put you ahead of the game when you finally put boots on the ground.

How to Scout Through Map Work

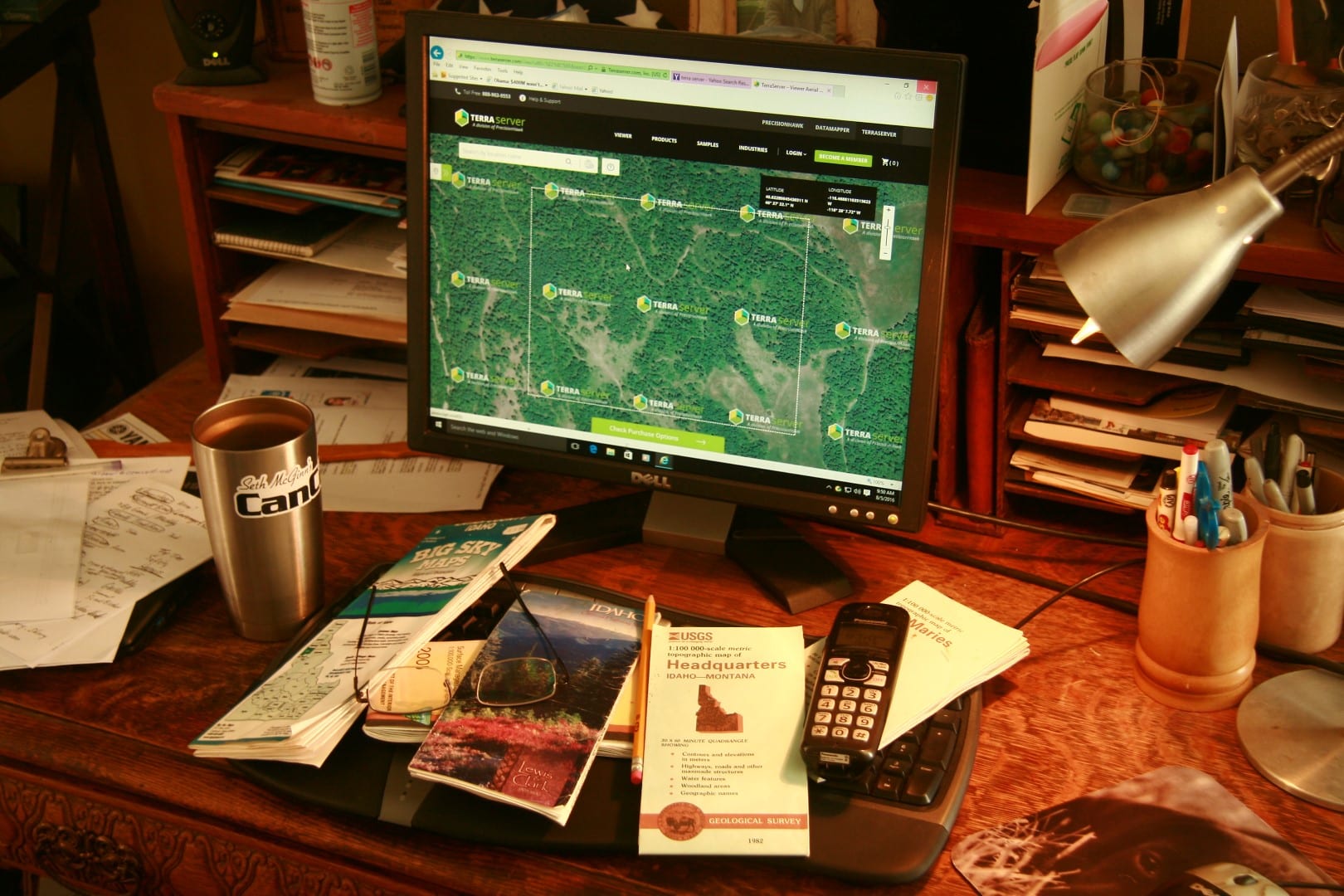

I’m pretty old fashioned. I still prefer to start the process of learning new ground with hard-copy maps and a standard-issue #2 pencil. I begin by purchasing maps from the Forest Service (http://www.fs.fed.us/visit/maps) or Bureau of Land Management—BLM—(http://blm.gov/[insert state abbreviation here]/onlineservices/maps/), and DeLorme Atlas & Gazetteer (www.delorme.com/mapstore), of my overall hunt area and state. Then, after narrowing prospects through these macro-view maps, I seek more detailed U.S. Geological Survey topographical maps. I prefer 1:250,000 scale, as they provide ample detail without requiring several dozen of maps to cover a single hunt unit. Use the USGS database (http://ngmdb.usgs.gov/) to determine which topo maps you’ll need and then purchase them at the USGS on-line store (http://store.usgs.gov/).

Use the Forest Service, BLM and atlas maps to get an overall feel for an area and establish starting points—access roads and trails, major watering sites, blank areas without roads and general ridgelines and mountain chains. Topo maps then provide added detail through contour lines, each representing a single elevation (spaced every 40 feet on 1:250,000 maps). Widely-spaced contours indicate flatter terrain, closely-spaced contours steeper ground. For instance, many lines running together show a cliff, very few lines a meadow or prairie. With experience topos begin to provide a virtual 3-D view of the territory you’ll be hunting, allowing you to concentrate on habitat types preferred by targeted species. Points of interest might include benches (widely-spaced tear-drop contours set amongst closely-spaced contours), saddles (contours creating an hourglass shape), meadows or mesa tops (widely-spaced contours surrounded by more closely-spaced lines) or serpentine ridgelines (snaking but parallel contours falling off into closely-spaced contours), just as examples. These are all topographic features that influence game movements. My maps, macro and micro, are always marked up with circled areas (remote, road-free spots), bolded arrows (deep saddles or watering sites), question marks (areas to check out once on the ground, or to ask local experts about) and penciled notes.

Topo maps can also help you negotiate rough terrain more efficiently. During 23 years of guiding big game hunters, before the internet resources we enjoy today, this was how we digested country and anticipated game haunts and movements.

How to Scout with Aerial Photographs

In the Brave New World bowhunters also have access to satellite imagery, providing real-time aerial photographs of just about any public land in the United States. The first few times I visited such sites, say 10 or 15 years ago, images weren’t updated very often. For instance, I once looked up my house in New Mexico and found the image was from 1967. More recently I’ve discovered images are updated much more frequently. The garage I built a few summers ago, for example, showed up within a few months of completion. Those who love conspiracy theories could credit this to greedy county tax assessors, but this can also be a boon to traveling bowhunters.

In a very basic sense, aerial photographs give you a better feel for the extent of meadows and fields where game animals such as elk and deer feed, perhaps hidden water sources not indicated on Forest Service or BLM maps; spots that could be a hotspot for early-season pronghorn. The whitetail hunter might be interested in forest breaks and openings where deer often stage before venturing into adjoining agricultural fields under the cover of darkness—which can also be excellent places to plant simple throw-and-grow food plots.

On a more detailed note, such insight can reveal recent forest fires (subsequent second growth attracting game looking for tender grass and forbs), new clear-cuts (on more than one occasion I’ve revisited an old hotspot to find it transformed into a stump field), how an older forest fire or clear-cut is progressing (depending on latitude and altitude, these places become game magnets at five to 10 years old), even new roads you were unaware of previously.

Look to user-friendly sites like USGS EarthExplorer (http://earthexplorer.usgs.gov), Terra Server (www.terraserver.com) and Google Earth (www.google.com/earth) for such insight.

Aerial photos can give you a great bird’s eye view of the ground you are planning to hunt.

How to Scout with Internet Resources

More recent developments take aerial photograph technology and add still more features. One of the most popular is ScoutLook Weather. The site’s most basic feature is to provide the ScoutLook Hunting App “ScentCone.” This allows pin-pointing a specific stand site on a map, clicking on the ScentCone feature and getting instant feedback on the downwind “stink zone” for that site. This information is updated hourly. You can also use this feature to see how the ScentCone changes each hour of the day or night, up to 10 full days into the future.

ScoutLook’s Hunting App also allows you to “connect the dots” on sign discovered once on the ground. “ScoutMarX” allows recording bedding areas, rubs, scrapes and other sign and then later using interactive satellite mapping to learn how it all ties together—helping you narrow down productive ambush sites. Successful hunts can also be geo-tagged for future reference, as well as the weather conditions that lead to that success. The Smartphone app is free, and downloaded at www.scoutlookweather.com.

Such technologies go hand in hand with remote-access trail cameras. Before investing in this pricey technology, assure the hunting area you have in mind has cellular service. Where I live in northern Idaho, for instance, remote-access cameras prove worthless, as there is zero cell service. But if service is available, and if you’re able to make a physical scouting trip into your perspective hunt areas and hang some cameras, not only can you access and monitor those cameras from home via e-mail or iPhone, but plug that information into a manufacturer’s server to overlay camera locations onto aerial photographs and topographical maps, fitting information gathered into a bigger picture. Bushnell calls their site DeerLab, Moultrie has their Moultrie Game Management site, Reconyx Buckview Advanced with Mapview Professional which embeds a GPS geo-tag and displays camera locations on Google Maps. These are but a few examples. If your favorite trail camera company offers a remote-access unit, odds are they also offer a management web site for a small fee, sometimes as part of your activation program. These cameras and the services required operate them cost more than standard trail cameras, but save money over time due to less burned fuel and time away from work manually checking scouting units.

Make Some Calls

Finally, once I have a decent idea of where I might hunt I get on the phone, seeking people who might know something of that area (state game agencies often supply e-mail contact info on their websites). State game and fish biologists are my first contact, as many spend a good deal of time afield, sometimes flying aerial surveys, and can be quite helpful at pointing you in the right direction—at least in general terms of, say, areas that get pounded by other hunters, and country that is often overlooked, as examples. Forest Service fire crews can prove another well of information, spending weeks in backcountry few trod. Make these calls only after investing in thorough investigation, as these public servants are typically quite harried and will not have a lot of time to chit-chat. Too, they are more likely to give you the time of day if they perceive you’re serious and have already put some effort into the project.

The wise hunter also references state game departments’ annual harvest statistics. For bowhunters, success rates above 25 percent for deer or elk, and 50 percent for turkey, are excellent places to concentrate efforts. The Natural Resources Conservation Service (formally Soil Conservation) is another worthwhile contact, a federal agency collecting data on the flora and fauna found in particular areas across the nation. While some effort is involved in sifting through their copious data, this agency’s reports can reveal specific food supplies, water and animal populations in very specific areas. Visit www.nrcs.usda.gov/ for contact information to regional offices.

My final piece of advice to any traveling bowhunter, especially when dealing with limited vacation time, is using one or two of your vacation days scouting on the ground before your actual hunt, even if that cuts directly into hunting days. You can spend your entire vacation hunting sign, or spend open season hunting game—it’s up to you.

By

By