A key factor in being able to select the right bow for the type of shooting or bow hunting you’ll be doing is having a proper understanding of what all the bow’s various pieces are and how they work.

In the following article we will break down the many components that work in harmony to make modern compound bows the smoothest, fastest and most efficient arrow shooting machines ever developed.

Cam System

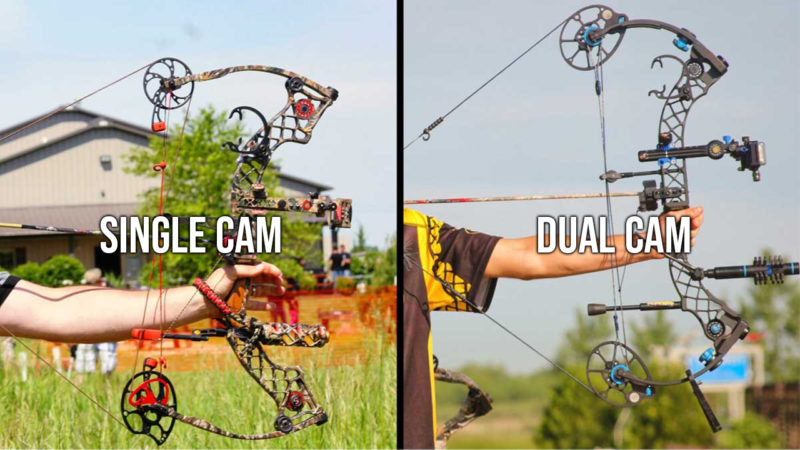

There are two major types of cam systems found on compound bows; dual cams and single cams. A dual cam bow utilizes two eccentric cams which are identical to one another on either end of the bow.

In most modern dual cam systems these cams are directly connected to one another via two cables.

Connecting, or slaving, the cams to one another ensures they are less likely to go out of time and thus be more reliable and consistent. This particular dual cam system is referred to as a “binary” cam.

While there are a variety of small differences between the manufacturers the basics of the dual cam system remain the same no matter who puts their name on it.

Single cam systems use a single, large cam on the bottom limb and an idler wheel on the top. The single cam feeds the string off the track as the bow is draw, while a single power cable that runs from the single cam to the top limb compresses the limbs to store energy.

Many people believe to their simple nature and lack of timing issues that single cam bows are easier to tune and shoot than dual cam systems. Although like most things in archery this is simply a personal preference.

Bow String & Cables

While it probably doesn’t need saying, the bow’s string what an archer uses to pull back the bow and what ultimately propels the arrow forward upon release.

Most dual cam systems utilize a single string and 2 cables, while a single cam system uses one very long string and a single cable. Modern bow strings are made from high tech materials such as Dyneema, which is used in everything from commercial fishing nets to bullet proof vests.

Most bow technicians recommend replacing your bow’s strings and cables every 2-3 years in order to maintain the best performance from your bow.

String Silencer

String suppressors are small rubber items that can be mounted either in between the strands of a bow string, or around it. They are designed to help dissipate noise and vibration caused by the bow string upon release.

Speed Nocks

Speed Nocks are essentially brass nocking points that are added to the bowstring in strategic locations to give it a little more power, and produce faster arrow speed. Depending on the bow model and manufacturer, these won’t be in the same exact location on every bowstring, but they will usually be in the same general area.

A lot of companies have recently been using Speed Nocks along with a shrinkwrap material, to show off the companies logo, and give a little more personalized look to the string.

Peep Sight

The peep sight is placed between the strands of the bowstring, and is generally held in place by a serving material. When at full draw, you will look through the peep sight and line it up with the sight as another anchoring point, for more consistent accuracy.

Peep sights come in many shapes and sizes. Target archer’s typically will use a peep sight with a smaller diameter for precise aiming. But most hunters use one that is a little larger because of possible low light scenarios, and the fact that animals have a tendency to move around. Using a larger peep sight allows you to stay on your target a little easier.

D-Loop

Modern archer’s have adopted the use of a “D-Loop” or “String Loop” when using mechanical release aids to shoot compound bows. The D-Loop is where the nock of the arrow attaches to the string, and where the archer connects the release aid to the bowstring.

It’s important to make sure the D-Loop does not move, or pinch together. If it does move, it can affect accuracy, or create “nock pinch” at the arrow of the nock. Nock Pinch occurs when the D-Loop knots are too close together, thus “pinching” the nock of the arrow, and lifting it off the rest when drawing the bow.

Center Serving

The “Center Serving” is made of serving material, which is a little stronger and tougher than regular bowstring material. The purpose of the center string is to prevent the wear and tear from regular use to affect the bowstring. It not only protects the string in the main usage point, but it also provides a better fit for arrow nocks.

Cable Guard

In order to keep the cables out of the path of the arrow, and the archer’s arm, a cable guard, or roller guard, is used. This guard pulls the cables off to the side in order to provide clearance for the arrow.

Most cable guards are either made from machined aluminum or a carbon fiber rod, and may use either a Teflon sleeve or metal rollers, to allow the cables to move when the bow is drawn and fired.

Bow Limbs

A bow’s limbs are connected to the riser and to the bow’s cam system. The limbs flex when the bow is drawn in order to help store energy which is then passed to the arrow upon release.

Most modern bow limbs are constructed of fiberglass or other composite materials with some being one solid piece and others consisting of several layers of various materials laminated together.

Some bow manufacturers use a single, solid limb design while others utilize split limbs. While solid limbs tend to be more prone to failure (cracking, splintering or breaking) some critics of split limbs say they are prone to warping or wearing differently thus affecting arrow flight and accuracy.

Most of today’s hunting bows feature “parallel” limb designs rather than the traditional d-shaped bows of years gone by.

The advantage of the parallel limb design is that each limb bends in an opposite direction and helps to offset noise and vibration during and after the shot.

Axle to Axle Length

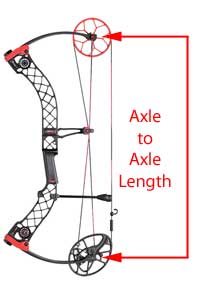

While axle-to-axle length isn’t a physical part of a bow, it is something commonly referenced when talking about bows. Commonly referred to as “ATA” length, this is the distance between the axles that run through the cams and limbs while the bow is at rest.

Most flagship bows these days seem to have about a 30″- 33″ ATA length. Most treestand hunters will prefer this length and possible something a little longer as well. And most ground blind hunters and people that hunt out west where there’s more hiking and climbing, will prefer a more compact bow, usually around 27″ – 30″ axle to axle.

Many target archer’s prefer using a bow with a longer ATA length, anywhere from 38″ – 42″ seems to be the norm. The reason they use a longer bow is because a bow with a longer ATA length will generally be more stable when at full draw. So in return, a smaller bow might be more compact and easier to lug around on a hunt, but you are losing a little bit of stability when choosing a bow that has a smaller ATA.

Limb Pocket & Limb Bolt

The primary job of the limb pocket is to hold the bow limb securely in place. Limb pockets are often made from machined aluminum, although sometimes they are made of durable ABS plastic or other materials.

The bow limb will rest inside the limb pocket, which is then bolted to the bow riser.

The limb bolt is what connects the limb pocket to the riser. Most limb bolts use a standard allen key to adjust them. Tightening the limb bolt will increase the draw weight of the bow, while loosening it will lower the draw weight.

When adjusting limb bolts it is important to adjust them both the same amount. Failure to do so can cause your bow to go out of tune.

Riser

The bow’s riser is the “middle” portion of the bow which contains the grip and is attached to the bow’s limbs. Most compound bow risers are made from aluminum and are either forged or machined.

The generally feature a multitude of cut-outs that serve to reduce the bow’s overall weight while still maintaining their strength and stability.

In recent years several bow manufacturers have developed compound bows with carbon fiber risers which are said to be stronger than aluminum risers while being extremely light weight and warm to the touch.

Many bow accessories are attached directly to the riser including sights, arrow rests, quivers, wrist slings, stabilizers and more. All mounting holes on a bow riser are universal size and placement, which ensures you can use virtually any accessory on any bow. The riser is truly the foundation of what is known as the modern compound bow.

Arrow Shelf

The place on a bow’s riser directly above the grip where the arrow rest is mounted is referred to as the arrow shelf. While modern compounds use an arrow rest to hold the arrow before and during the shot, in traditional archery the arrow is most commonly shot directly off the shelf, which is where the name comes from.

Grip

The bow’s grip is where you hold the bow while shooting. Grips can be made from wood, plastic, rubber or even metal.

Each bow’s grip will feel different so it is important to try and find one that feels right in your hand. There are also a variety of custom grips on the market that offer flexibility in both size, hand position and color.

String Suppressor

First made popular in the mid 2000’s the string suppressor mounts directly behind the bow’s stabilizer and is most commonly consisting of either a metal or carbon fiber rod with a rubber bumper on the end.

The bumper serves to stop forward string travel after the shot which helps reduce noise and vibration.

Additionally, a string suppressor can help prevent unnecessary slapping of the bow string on the archer’s forearm. Most technicians recommend a gap of 1/16″ to 1/8″ between the rubber stopper and the bow string. Additionally, it is recommended to always have your bow string served where the bumper will make contact. This helps prevent unnecessary wear on your string.

Stabilizer

Most bows don’t come with a stabilizer, but they all come with the stabilizer mounting hole. This universal fit allows nearly any stabilizer to be used with most bows.

The purpose of a stabilizer is to stabilize the bow when at full draw, and absorb vibration on the shot. Most hunters will use a stabilizer from 4″- 12″ in length. This allows for good stabilization while also maintaining the ability to move around easily in the woods or when at full draw.

Target archer’s tend to use really long stabilizers anywhere between 24″ – 48″ in length. Having a longer stabilizer isn’t very beneficial in a hunting setting, but since a target archer typically has a small spot they need to hit, and no obstacles immediately in front of them. They can get away with using a long stabilizer.

Wrist Sling

Many archers like to use a wrist sling when shooting their bow. This sling mounts between the bow’s riser and stabilizer, and serves to hold your bow in place should you lose your grip during the shooting process.

Wrist slings typically don’t come with your bow from the factory and are aftermarket additions. They are available in a variety of sizes, colors and materials to suit the individual archer’s needs.

Brace Height

Measured as the distance between the throat of the bow grip (the deepest part) and the string, brace height is often used as an indicator of speed and forgiveness.

Bow’s with short brace heights (under 6 ½ inches) are generally considered less forgiving, as they can be more sensitive to flaws in the archer’s form. Bows with longer brace heights, those great than 6 ½ inches, are referred to as more forgiving and easier to shoot.

By

By