When the bull elk lost its balance, shuffled sideways and collapsed in a ground-shaking, wood-splintering crash, I knew better than to think, “Well, that was easy!”

Yes, it was only the second day of my annual two-week bowhunt in the Targhee-Caribou National Forest. And yes, my arrow had to fly only 18 yards to the bull’s chest.

But the only things that felt effortless that evening was releasing the arrow, and appreciating the many factors that made everything else look so easy.

First, the site itself is one of only two deep-woods elk wallows our small group has found in 12 seasons of hunting this area. My friend Chris White and I found this site during the 2016 season after chasing a bugling bull across the nearby mountainside a few hours before.

This soggy wallows in Idaho lured a bull elk into bow range

After the bull eluded us, we cut through this wooded draw to reach our starting point. We had crossed this draw several times the previous four Septembers, but always higher up where it opens into a meadow of sage brush, arrowleaf balsamroot and several plants I don’t recognize. Nothing near the meadow suggested small springs and wallows awaited discovery farther down the mountain, or maybe we just didn’t know what to look for.

Second, after finding the slits of black mud zigzagging through the draw, White and I staked out the wallows a couple of times a year ago. But we saw no elk. They neither came in to drink from the site’s soup-bowl sized puddles, nor roll in its musk-infused mud to thwart flies and cool their hides. Given the thermal currents and swirling winds blowing through the draw, we figured we needed a treestand to thwart the elk’s superior nose.

A young bull elk stops to investigate the sound of a clicking camera shutter.

Third, it’s not easy hauling a treestand 1.75 miles and 1,200 feet up the mountain from camp. Still, it had to be done, and so I lashed it atop a cargo pack, stuffed a safety harness into the pack’s compartment, and made the trek in 90-degree temperatures two days after Mark Endris and I set up camp Sept. 1. Once reaching the meadow about the wallows at midafternoon, however, I was too tired to install the treestand.

After hunting the mountaintop meadow till dark and returning to camp, I ate dinner with Endris and went to bed. Five hours later I awoke to the 3:30 a.m. alarm on Labor Day, and reached the meadow at first light. A cow elk strolled by about 70 yards away at 7:10 a.m., and a decent 4-by-4 bull took much the same path an hour later.

When 10:30 a.m. arrived, I moved downhill about a quarter-mile to the wallows. I chose a mature pine uphill about 20 yards, thinking we could reach it quietly from a hilltop game trail above. The pine looked solid and healthy, unlike its many beetle-killed brethren nearby. And so that’s where I hung the old aluminum treestand made by a company no longer in business.

That task wasn’t easy, either. Hanging a treestand never is. After descending, I sat beneath the boughs of an old Douglas fir, ate lunch and napped.

Friends who grew up bowhunting elk say midafternoon isn’t too soon to sit on a wallow, and so I climbed in the treestand at 3 p.m., determined to stay till dark. Five-hour sits can seem an eternity unless when you’re confident it’s your best option.

About 6 p.m., white chalk dust from my wind-checking bottle showed evening thermals blowing downhill. That meant elk approaching from far down the ravine might catch my scent. That doesn’t mean they will, of course. Even though that’s the direction I expected elk to come from, I knew I could be mistaken. Big country like this tends to mock assumptions.

At 6:30 p.m., wood snapped nearby. Uphill 30 yards away a 4-by-5 bull elk stepped into the muddy slit leading to the wallows. After sniffing the pungent dirt and nosing around for a sip of water, the bull stepped onto a nearby trail and walked downhill.

Pulling my bow to full draw, I looked through the string peep, aligned it with the front pin sight, and tracked the bull’s chest as it drew closer. I planned to stop it with a mouth call when it was broadside in just two more steps. Instead, the bull turned 90 degrees to face me and walked back into the muddy slit. It resumed sniffing and sipping as it faced me head-on, a shooting angle that looked too risky for my tastes.

I relaxed from full draw to wait.

And wait.

And wait.

Finally after about three minutes the bull turned to look downhill. When it looked away, I drew the bow again, waiting, hoping it would turn farther yet to expose a broadside target. When it did, I shifted my aim behind its shoulder and noticed a tall green, fork-stemmed plant inches in front of the bull’s heart. The “V” in the stem framed my aiming point.

That’s where my arrow struck. The bull jumped from the gully, trotted about 50 yards across the draw and stopped. Seconds later, it was all over except the photographing, skinning and boning. Those chores took until 12:45 a.m. to finish. I then hiked down to camp, where I told my story to Endris at 2:20 a.m.

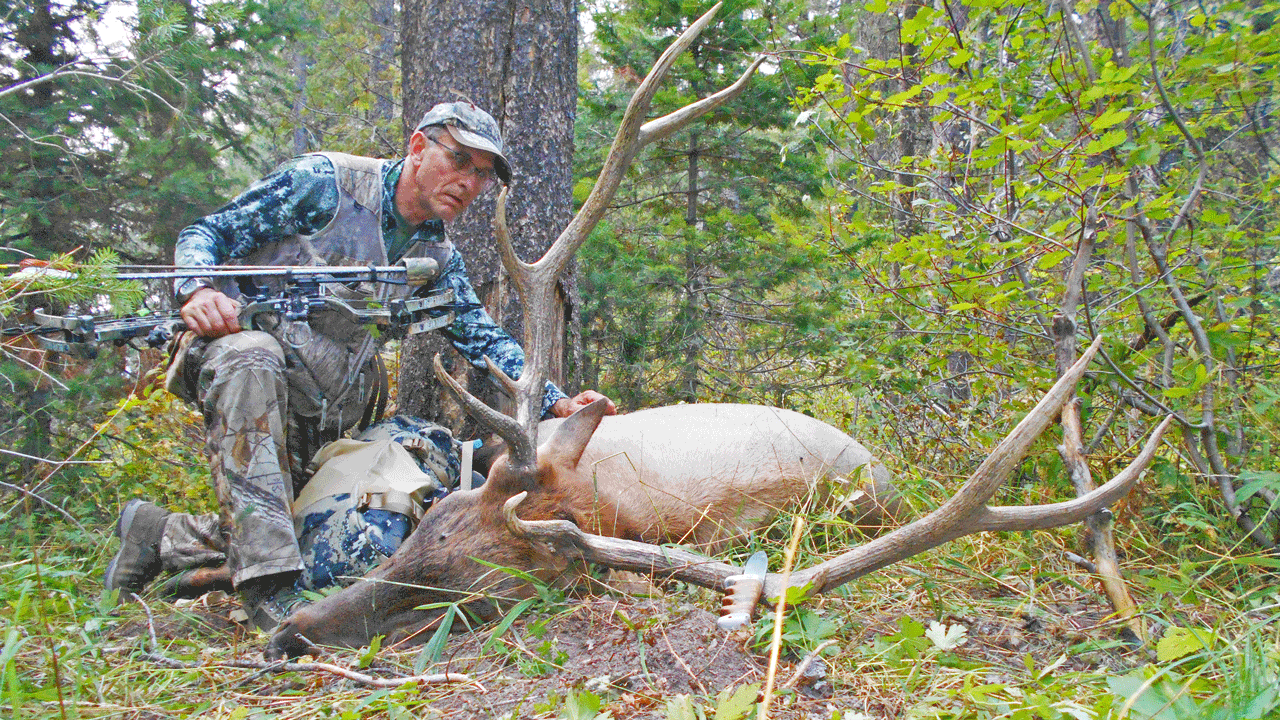

Patrick Durkin with a bull elk he arrowed on Labor Day in southeastern Idaho.

We got up four hours later; prepared cereal, coffee and oatmeal; packed meat bags and freighter packs; and hiked back up to the kill site. A vulture, blue-flies and paper wasps were already at work on the bull’s bones, but its venison sat untouched inside a giant game bag beneath extra clothes I had assigned overnight guard duty.

Patrick Durkin’s do-it-yourself elk camp in southeastern Idaho’s Targhee-Caribou National Forest.

Endris and I hauled meat and the heavy hide till dark that day, but only got one-third of it into ice-chilled coolers by dark. The rest we cached overnight about a half-mile and several hundred feet above camp. I hauled those bags in early the next morning. With ice forming the top layer, the meat filled two 65-quart coolers.

I don’t know if all that work and all those decisions make elk venison taste all the sweeter. All I know is this: I can’t wait to try it again in 2018, and I don’t expect it to be any easier.

By

By